Mattress producers find strength—and better bedding—through cooperation

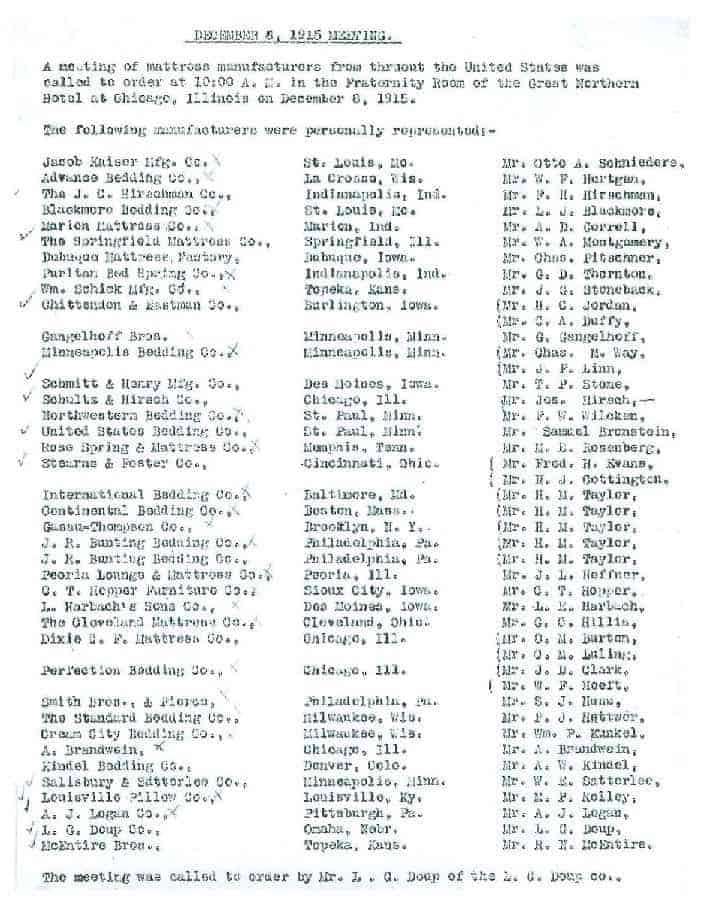

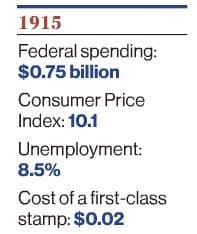

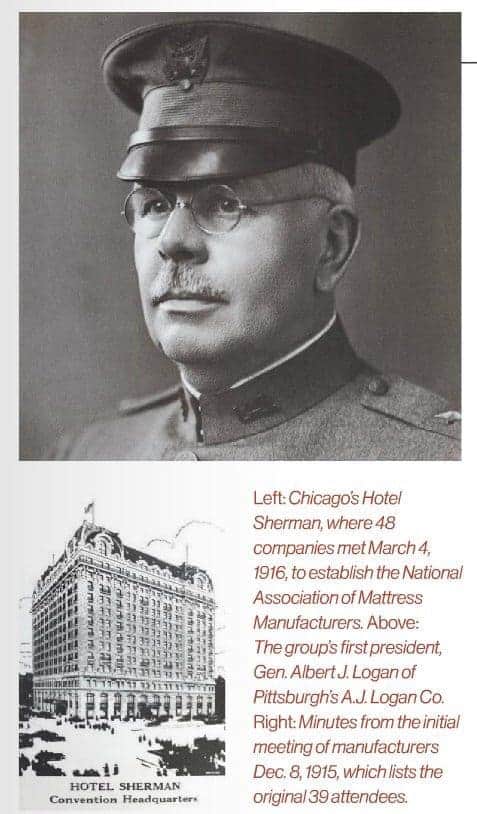

On Dec. 8, 1915, 39 mattress manufacturers gathered at the Great Northern Hotel in Chicago. On a day-to-day basis they were fierce competitors, but they were facing threats they couldn’t stamp out on their own: It was time to find ways to work together.

Most troubling was a sense of lawlessness contaminating the industry. Without standards governing sizes, constructions, advertising—really anything at all—disreputable companies harmed the good standing and livelihood of honest producers. Lawlessness of another kind was on their minds too: A war in Europe seemed destined to spread.

The inaugural era of the association was bookended by two horrific world wars and economically centered on the heady enthusiasm of the Roaring Twenties, followed immediately by the devastation of the Great Depression. With companies drawn together, the industry weathered these events, strengthened by the adversity and buoyed by the knowledge that, through association, bedding manufacturers were better prepared for whatever they would encounter next. From its earliest days, the association served as an advocate, arbitrator, communicator, marketer, troubleshooter, promoter and peacemaker. It provided continuity and even inspiration at times when the industry needed it most.

To trace the association’s history and celebrate ISPA’s centennial, BedTimes will run a series of articles over the course of the coming year. In this issue, we chronicle the association’s infancy and early adolescence—the period from 1915 to 1940. In June, August and November, we’ll examine subsequent 25-year blocks and watch the association grow and mature. A caveat: No project of this type can present a complete history of 100 years. Our goal is to provide you with a sense of the era and the association’s evolution, with a focus on what kept industry leaders up at night—and what gave them pleasant dreams.

Initial objectives of the association

✦ “To establish such confidence between manufacturers of mattresses as shall tend to maintain a high standard of fairness in competition and bring into the industry a good fellowship

✦ “To encourage the careful study of costs

✦ “To encourage an honest observance of state bedding laws and to work for uniformity in such laws

✦ “To encourage the proper labeling of mattresses and to discourage in every possible way any practice of deception

✦ “To do such other things or to adopt such measures as shall tend to place the mattress manufacturing industry on a high plane.”

(Published in the inaugural issue of The National Bedding Manufacturer magazine, August 1917)

Laying down the law

At the advent of the association, mattress manufacturers operated in a largely ungoverned environment without regulations on mattress contents, sizes, pricing practices or advertising. Unscrupulous companies took advantage, often by selling old bedding as new, filling mattresses with questionable materials and other equally egregious practices. Maryland established the nation’s first sanitary bedding law in 1906, but it was an outlier. NABM wanted other states to follow suit. Such laws had two equally important goals: improving the quality of bedding products overall and building consumers’ trust in the industry.

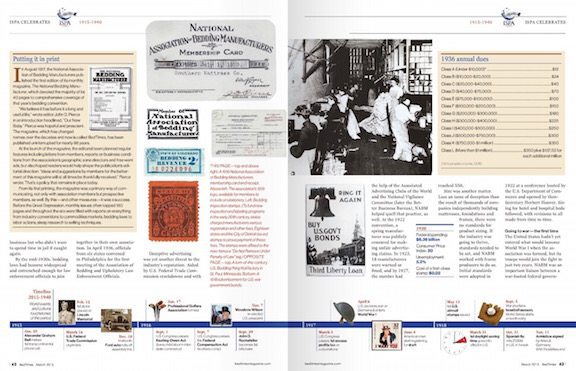

The first big success in what would be a long-term NABM campaign came when Iowa, Michigan and Tennessee enacted laws around 1917. Others quickly followed and, by 1923, 27 of the then-48 states had adopted bedding regulations.

The association didn’t hesitate to criticize unprincipled manufacturers. A 1924 article in the industry magazine, The National Bedding Manufacturer, opined about a producer who sold mattresses as new when, in fact, they contained components gleaned from old hospital bedding: “He is a disgrace to the industry of which we are ashamed to say he is a part. His vile action does not injure himself only. It casts its reflection on the entire industry and causes other factories in the locality to suffer. … Let the clean-up of the industry go on until every man who so disgraces our industry is behind the bars or put out of business.”

The pages of the magazine read like a police blotter as NABM called out manufacturers who violated the bedding laws the association was trying so hard to get enacted and enforced. In virtually every issue, the editors ran often lengthy state-by-state rundowns of people convicted under bedding laws. As early as 1926, NABM estimated there were nearly 200 arrests and convictions annually.

Violators’ products typically were:

✦ improperly or insufficiently labeled,

✦ missing required labels and stamps altogether

✦ and/or fraudulently tagged as containing one type of filling or component when the products actually contained something else.

Fines ranged from $10 to $100, though in states like New York they could go as high as $500. Some states, including California, had success handing down suspended jail sentences, which had the desired outcome of cutting down on repeat offenders who viewed fines as nothing more than a regular cost of doing business but who didn’t want to spend time in jail if caught again.

By the mid-1930s, bedding laws had become widespread and entrenched enough for law enforcement officials to join together in their own association. In April 1936, officials from six states convened in Philadelphia for the first meeting of the Association of Bedding and Upholstery Law Enforcement Officials.

Deceptive advertising was yet another threat to the industry’s reputation. Aided by U.S. Federal Trade Commission crackdowns and with the help of the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World and the National Vigilance Committee (later the Better Business Bureau), NABM helped quell that practice, as well. At the 1922 convention, a spring manufacturer was publicly censured for making unfair advertising claims. In 1923, 18 manufacturers were warned or fined, and by 1927, the number had reached 550.

Size was another matter. Less an issue of deception than the result of thousands of companies independently building mattresses, foundations and frames, there were no standards for product sizing. If the industry was going to thrive, standards needed to be set, and NABM worked with frame producers to do so. Initial standards were adopted in 1922 at a conference hosted by the U.S. Department of Commerce and opened by then-Secretary Herbert Hoover. Sizing for hotel and hospital beds followed, with revisions to all made from time to time.

Going to war—the first time

The United States hadn’t yet entered what would become World War I when the association was formed, but its troops would join the fight in just two years. NABM was an important liaison between a war-footed federal government and mattress manufacturers. War efforts commandeered both natural resources and labor, leaving companies with material shortages (particularly steel), rising prices and hollowed-out workforces. At the same time, government officials knew that a country at war would need a thriving, consumer-oriented manufacturing sector when the war did indeed come to an end.

In advance of the 1918 convention, NABM made it clear to members that the war was a threat to the industry’s very future: “It is your duty to attend this convention as a member,” the editors of the magazine wrote. “It is not only your duty to self and your company, but it is your duty to your industry and a patriotic duty (italics original). We are at war and our government is asking that every industry be organized. Some times are coming when each industry will stand or fall largely in proportion to its efforts as related to other industries (and) ability to cooperate with the government.”

Assuming a new name

The association’s role as mediator, protector and industry advocate when dealing with the federal government extended well beyond matters of war.

In its very formation, NABM—and the host of other industry groups emerging in the early decades of the 1900s—faced possible federal scrutiny. The Sherman Act, the first major piece of anti-trust legislation, had little practical effect on U.S. businesses for the first decade after its passage in 1890. But that changed in 1904 when President Teddy Roosevelt pressed the U.S. Justice Department to dismantle the Northern Securities Corp.—a decision later upheld by the Supreme Court.

The Roosevelt administration was intent on stamping out monopolies, unfair competition and price fixing, but industries and trades were allowed to work together through “cooperative competition.” NABM’s early leaders were well aware of the fine line between the two and issued caveats to members like this one in August 1917: “It should be thoroughly understood by the members of the Association that all information reported to the Association or distributed by it is purely statistical and pertains only to past and closed transactions; and that no part of the machinery of this Association will be permitted to be used to fix prices for the sale of mattresses, to divide the territory, limit the product of manufacture, or limit or control competition; and no information shall be collected or distributed respecting any prices which any member intends or expects to ask under any circumstances whatsoever.”

By the early 1920s, “certain misguided” trade associations were, indeed, being publicly criticized and federally investigated for violating anti-trust laws and functioning “merely as a new form of the old-time trusts and price fixing bodies,” editors of the magazine reported. NABM leaders began to worry that the organization’s own reputation was being harmed—pardon the pun—by association and voted in 1923 to rebrand.

“Our organization stands for higher standards, public health, sanitary products and honesty in merchandise,” according to a February 1923 article announcing the change. “It is believed that the new name—the Better Bedding Alliance of America—indicates much more clearly and favorably the real purposes of the Association.”

The perils of prosperity

The United States—and the mattress industry along with it—suffered through a short post-war recession and then a more severe one in 1920 and 1921. But welcome prosperity quickly followed. The association itself grew to 199 members by decade’s end, and the value of bedding shipments—from some 838 companies—reached a record $100 million in 1927 and then $123 million in 1929. (The numbers come from statistics compiled by the Department of Commerce under a program initiated by NABM in 1921 but later criticized relentlessly by the association, which said it failed to include statistics from as much as half of the nation’s producers and thereby vastly underrepresented the size of the bedding market. The numbers typically were reported in the magazine with a stipulation like this: “While the information is quite valuable in giving some idea as to the scope of the industry, nevertheless, it is not wholly accurate.”)

But the good days would come to an abrupt end with the stock market crash in October 1929. By 1933, the bedding market had lost half its value—sales were down to $59 million.

The mattress industry was not alone in reeling—and not just from the economic collapse: The New Deal ushered in by President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration changed the business landscape forever, codifying a host of new rules and regulations for everything from labor to pricing.

Initially, the association was supportive of the New Deal and its National Industrial Recovery Act, which regulated industries with the goal of reversing deflation and keeping workers employed. Under the NIRA, the association adopted the Bedding Code, which set industrywide fair trade practices (including a ban on second-hand materials in new mattresses) and labor standards, essentially paying workers higher rates for fewer hours.

While acknowledging that not everyone was a supporter, the magazine editors wrote in February 1934: “Backing the New Deal is not idealistic. It’s self-preservation, pure and simple. … No great reform was ever achieved without travelling through hell and high water. So far, Roosevelt and his program, despite caustic press criticism, have ridden high wide and handsome.”

But industry favor turned later that year when the government, in an effort to create jobs, proposed becoming a bedding maker itself and producing 2 million “relief” mattresses. The organization rallied, enlisting the help of both sympathetic lawmakers and other trade groups: They succeeded in getting the number cut in half.

By early 1935, the association was increasingly frustrated by its dealings with the National Recovery Administration, suspicious of any new federal legislation and disappointed that the required Bedding Code had not, among other things, done more to raise prices for finished mattresses. When the Supreme Court ruled the mandatory codes section of the NIRA unconstitutional, the Bedding Code—and other codes like it—were legally invalidated. The bedding group then dissolved, but re-established itself, reverting to its previous name, the National Association of Bedding Manufacturers.

Despite the turmoil, the economy began a slow rebound and, by the end of 1935, bedding sales had increased to $84 million—still far below the 1929 high, but it was something. Accordingly, the industry turned its attention to other issues such as a push to get consumers to replace their full-size beds with two twins—because two beds are better than one.

But, regardless of how much the industry might have wished for it, a “Roaring Forties” was not to be. By the end of the decade, new threats were looming in Europe. The industry’s next era would begin just as this one had—with a world war. ✦

Read the entire seven-part special section, “ISPA Celebrates, Part I–1915-1940,” in the March BedTimes digital edition.