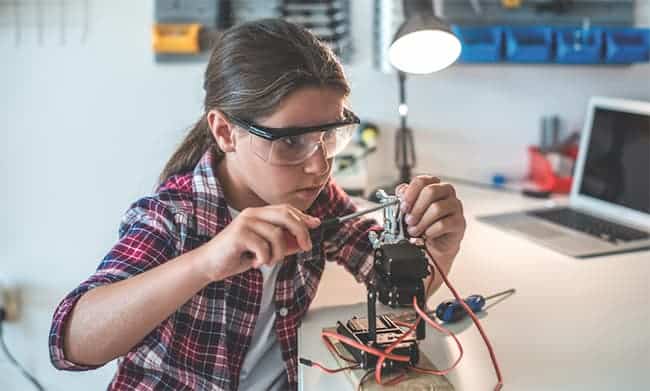

Follow these tips to attract and retain your next-generation labor force

BY BARBARA T. NELLES

In these post-recessionary times, with many hoping to see a U.S. manufacturing rebirth, the moment is right to retool recruitment and retention practices for your factory floor.

- How do you attract mechanically inclined millennials to your machine maintenance crew?

- What is the best way to replace retiring equipment operators and technicians whose skills your company has depended on for years?

- How do you make certain rank-and-file workers are motivated to stick around for the long term and that their skills remain up to date?

Many in the bedding industry are asking themselves these questions. They have come to find that in an improving economy, poaching experienced staff from the competition isn’t sustainable. For employers, and for the mattress industry as a whole, to prosper and grow, its talent pool must grow, too.

BedTimes spoke with a cross section of mattress manufacturers and other industry members, both on the record and off, about staffing issues, especially for the factory floor. Most confirmed that it’s a scramble to fill open positions for key roles and to hold onto those employees.

“Labor shortages and labor retention are issues that are talked about constantly around the world in manufacturing,” says Paul Block, vice president of sales strategy and product planning for Global Systems Group, the machinery division of Carthage, Missouri-based Leggett & Platt Inc. “We need to raise awareness and open the conversation.”

BedTimes tries to do that here. We don’t have all the answers, but here are some observations and ideas from within and outside of the bedding industry on how the mattress manufacturing industry can and should attract a new generation of workers to its ranks.

Skills gap or training lack?

Google “skills gap” and you’ll see a flood of news stories beginning around 2011 and continuing through today. The doom and gloom about America’s underskilled labor pool makes for good headlines, and observers have been painting the situation as dire since the end of the Great Recession.

In a 2015 report, “Skills Gap in U.S. Manufacturing,” the Washington, D.C.-based trade group the Manufacturing Institute says 2 million production jobs will go unfilled in the next decade because workers lack the right skills, and 75% of manufacturing executives say the skills gap is hampering growth, productivity and the adoption of new technologies.

But, Peter Cappelli, the George W. Taylor Professor of Management and director of the Center for Human Resources at the Philadelphia-based Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, will have none of it. He’s a frequent speaker and debunks the idea of the skills gap in his 2012 book, “Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs: The Skills Gap and What Companies Can Do About It.”

Cappelli urges employers, especially those in the manufacturing sector, to take responsibility for investing in employee training and development, and he provides cogent advice on getting those open positions filled.

For starters, Cappelli advises employers to ask themselves five questions:

- No. 1: Do you consider only candidates who’ve done virtually the same job you’re hiring for? It’s called the Home Depot view of the hiring process—filling a job vacancy as you would if searching the hardware aisle for the precise replacement part to fix your washing machine. The applicant must have the exact experience and qualifications of the previous employee. This sharply narrows your pool of applicants, and you may not get the best person for the job. Instead, hire people with basic skills and the right attitude, and give them a 90-day probationary period to see if they have the ability to do the job with some ramp-up time.

- No. 2: Are you using hiring software? With resume-scanning software and prescreening questionnaires, it’s likely you’ll eliminate lots of qualified applicants. This is especially true when job descriptions detail unreasonably long lists of required skills and experience. The resumes of qualified candidates who happen to lack the most trivial or easily learned skills may never make it to your inbox.

- No. 3: Is it just too difficult to decide? Thanks to plentiful internet-based recruitment tools, you may be over searching when filling open positions. If there are more applicants than you bargained for, avoid the tendency to keep searching until you find the perfect candidate.

- No. 4: Do you routinely rule out the unemployed, the underemployed and older workers? Don’t disregard these categories of able applicants who may have the skills, temperament and proven track record you need.

- No. 5: Are you paying a fair wage? When was the last time you increased your hourly rates? Check the current International Sleep Products Association’s “Mattress Industry Production Wage and Management Compensation Survey,” as well as the Bureau of Labor Statistics, to see how your company’s pay scale stacks up against average wages across the industry and the country. If candidates are turning down job offers or if you regularly lose employees to less strenuous service sector jobs, it’s time to rethink your payroll. (The ISPA wage survey is available free of charge to ISPA members. For more information, see story to the left or visit SleepProducts.org.)

Question No. 1 is arguably the biggest obstacle among manufacturers looking to fill vacant medium and higher skill jobs. But, post-recession, with so many employers looking to “hire in” highly specific skills, it’s no wonder many come up short-handed, according to Cappelli and other employment experts.

Many companies cite high employee attrition as the reason they can’t afford to invest in training recruits or bringing in new blood.

The manufacturing sector, in particular, has backed off from providing work-based training programs. Yet, a generation ago, most manufacturers ran apprentice programs, Cappelli says. Yes, those apprentices were expected to spend their careers with the company and, today, there is no such expectation.

But, if industry does not invest in attracting and developing new talent, who will keep tomorrow’s manufacturing plants at peak production?

Nurturing new recruits

Since classroom learning is both insufficient (and largely unavailable) for preparing students to take on a manufacturing job, employers should work with schools to create hybrid learning opportunities that include on-the-job experience, Cappelli says.

Some companies have successfully tackled the recruitment training process by developing their own in-house training programs. One company, Bloomington, Illinois-based Mechanical Devices, was unable to fill machinist positions so it created a 10-week training program at its plant and 16 of 24 trainees accepted to the program made it to graduation and were hired.

A trucking company in Salt Lake City used a shared training program model. When it couldn’t hire enough drivers, it set up a driving school at its truck yards and offered a job to anyone who could complete the training. Trainees took the course on their own time without compensation. Over an 18-month period, the program graduated 440 drivers.

Another option—formalized apprenticeship programs—may make sense for the bedding industry, especially for the technicians tasked with maintaining and repairing industrial sewing equipment. There is a dual benefit: Apprentices don’t have to pay up front for their training, and employers benefit because they pay apprentices less than the value of their work. At the end of the training, apprentices have gained the specific skills they need to do the job. These programs can be created in conjunction with a local community college or technical school.

Partnering with community colleges

Many companies are partnering with the public sector at the state and local level, especially in the development of training and retraining programs offered at increasingly popular community colleges.

- Ten years ago, at Reading Area Community College in the Rust Belt town of Reading, Pennsylvania, area employers and high schools partnered to create the Schmidt Technology and Training Center. The goal was to replace a quarter of the region’s manufacturing workforce set to retire in the coming decade and remove the stigma associated with manufacturing jobs, according to a story at Marketplace.org. Today, graduates have their pick of employment among the region’s 500 manufacturing companies that make everything from batteries to surgical supplies, with starting wages of $20 to $30 per hour, plus benefits.

- When Erlangen, Germany-based engineering company Siemens Energy opened a gas turbine manufacturing facility in Charlotte, North Carolina, it received 10,000 applicants for 800 posts but found that less than 15% of candidates could pass a required reading, writing and math skills test. In 2011, Siemens established an apprenticeship program for area high school seniors comprised of four years of on-the-job training, in addition to classwork at a nearby community college. Program graduates earned an associate’s degree, incurred no student debt and landed jobs paying about $50,000 per year.

- Machinery maker John Deere, headquartered in Moline, Illinois, works with a number of community colleges around the country to offer a curriculum that trains technicians for its dealer network. The company donates farm equipment to the schools for training purposes, and students get hands-on work experience by being sponsored by a nearby John Deere dealership. Students work for roughly half the program and most graduate in two years with a job offer in hand. Starting salaries average just less than $40,000.

How much should you pay?

Members of the International Sleep Products Association are at a distinct advantage when determining how much to pay their employees if they participate in ISPA’s biennial “Mattress Industry Production Wage and Management Compensation Survey.” Participants receive a free copy of the report, which offers aggregate industry data, in addition to company-specific data benchmarked against industrywide and peer data. Nonparticipating ISPA members can purchase the survey for $500.

“You can use the knowledge gained from this report to negotiate competitive salaries and benefits for your plant personnel, and you will know how you compare with your peers on hourly and piecework wages for your geographic area,” says Ryan Trainer, ISPA president.

The next ISPA wage survey will begin in October. For more information, contact Jane Oseth at [email protected] or visit the website.

Where have all the mechanics gone?

Every mattress manufacturing plant needs a maintenance crew to keep machinery up and running. Among the mattress producers BedTimes spoke with, crews range from two to 20, depending on the facility size, and ideally, have the talent to work on the industry’s close to 100 different types of equipment.

Unfortunately, many don’t.

The fact is, the experienced industrial sewing machine mechanics, who decades ago moved from offshored apparel manufacturing into the bedding industry, are rapidly retiring—leaving many companies scrambling.

Bill Holland, maintenance manager for Serta licensee Serta Mattress Co., a division of Salt Lake Mattress based in Salt Lake City, is hoping for a new generation of mechanically inclined millennials to fill their shoes, but he sees the need for a concerted industry effort to attract them.

“Frankly, I’m worried,” Holland says. “We need to get the word out. These are good-paying jobs. If we’re going to continue to manufacture in this country, then we need to have that pool of people out there.”

Most mattress makers say they are having some success hiring mechanics from outside the industry. Most agree it takes about five years for a green recruit to be considered a seasoned technician. And there always is the nagging worry that the newly trained will be hired away by the competition.

When Restonic licensee Johnson City Bedding, in Johnson City, Tennessee, lost its longtime maintenance mechanic, company president Bob Parker hired a technician with “electrical and pneumatics skills” and trained him in sewing.

“He jumped in and developed into a top-notch sewing machine mechanic,” Parker says. “Online training has been a big help—especially videos from machinery companies on maintenance and adjustments, as well as videos from around the world. Odds are, if you’re having a problem with a machine, there’s a video from someone who has fixed it.”

Ongoing information technology training also is a necessity so that mechanics have the skills to properly maintain and troubleshoot increasingly complex, computer-driven equipment—and prevent breakdowns and work stoppages.

Holland and others hope to see major manufacturers develop corporate training programs for their mechanics, as well as formalized apprenticeship programs in partnership with technical schools.

“When I train someone, I have them looking over my shoulder—and better yet, have them do it themselves. Hands-on is always better because you will remember it,” Holland says.

Summer camp for the mechanically inclined

Getting young people to consider a career in manufacturing is the goal of Nuts, Bolts & Thingamajigs, a grant program for summer camps with a mechanical focus. The nonprofit foundation was established by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International, a trade group based in Elgin, Illinois. This year, it made awards of $1,000 to $2,500 to 63 summer camps held at community and technical colleges.

NBT provides ongoing support—from curriculum guides to T-shirts—to camping programs that have qualified for three years of funding assistance and become self-supporting. It also gives scholarships to students attending community colleges, technical colleges and trade schools to pursue training leading to careers in manufacturing.

Qualifying camps target students from middle school to high school and provide practical applications of math, science and engineering principles. Students gain hands-on experience working with new technology to design and manufacture a product they can take home, and they participate in field trips to local manufacturing plants.

“It is NBT’s mission to find the workforce of the future, and summer camps introduce young people to manufacturing in a way that sparks their passion for making things,” says Warren Long, commodity manager of Briggs & Stratton Products Group and NBT board chair. “Camp participants learn about the companies in their area, and they leave camp excited and encouraged to pursue the skills training they need for a successful career in manufacturing.”

Hiring advice from the mattress plant floor

Without them, candidates go elsewhere.

“Working in a mattress plant can be physically demanding, and there are competing employers out there, such as fulfillment centers (where work is less strenuous),” says Bob Parker, president of Restonic licensee Johnson City Bedding in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Many manufacturers find hiring success with employment agencies, especially with the temp-to-hire model, where the agency supplies vetted candidates who have a trial period on the job.

Bill Spudis, president of Spring Air and Therapedic licensee Pennsylvania Bedding in Scranton, Pennsylvania, uses employment site Indeed.com and pays bonuses to employees who refer candidates. “They get a second bonus if their referral remains with the company for a full year,” he says.

John Repucci, international sales manager for Asheboro, North Carolina-based Piedmont Mattress Equipment, which repairs machines and supplies refurbished equipment, adds: “It’s hard work—new recruits need to know they’ll be eligible for yearly rate increases as their skills and speed improve.”

For plants that incentivize certain operators—such as tape-edge operators, assemblers and upholsterers—with a piece rate, it’s important also to reward supporting staff, such as material handlers.

In addition, mattress manufacturers are investing in “deskilled,” automated equipment to make factory work less strenuous and to alleviate repetitive-motion injuries—and employee attrition.

Cross-training, whenever feasible, is another tactic to remove some of the monotony of repetitive work.

“It’s a core value for us,” Parker says. “The majority of people embrace cross-training because they also realize they are of more value to the company. Whenever someone is on vacation, we view it as a cross-training opportunity for other employees.”

Chicago-based A. Lava & Son, a contract sewing and product assembly company with 500 employees, cross-trains from machine to machine, as well as on the company’s computer systems and all of its different processes, says Vice President Adam Lava. “That way, when people are on vacation or maternity leave, there is always backup to fill their job.”

The bedding industry’s just-in-time manufacturing requirements put unique pressures on those who work in production, Lava adds. Throughout the industry’s supply chain, there is tremendous stress on operations staff because “no one wants to hold inventory, and everyone promises each other 24- to 48-hour delivery.”

When Ms. Consumer doesn’t receive her new mattress in 24 hours, it’s too easy to make the production staff “the fall guys,” he says, which leads to rapid burnout and attrition on the plant floor.

“We don’t fire people for making mistakes. We aren’t yellers and screamers, and we’re not big on micromanaging,” Lava says. “We listen to everyone’s opinion; we reward people for exceptional work and we promote from within.”

Equipment makers to the rescue

There are no technical schools or community colleges offering coursework or certificates in the operation and maintenance of industrial sewing equipment, or any of the other big, complex machinery found in bedding plants. But there are the industry’s major machinery suppliers.

Equipment companies are a vital training resource for mattress manufacturers looking to get new recruits up to speed by offering generalized and machine-specific training and ongoing support in equipment operation. Help is available in-person, in training classes, online, over the phone and even via Facetime. When a mattress maker buys a new piece of equipment, the installation includes on-site training for operators and possibly follow-up training. In-depth, machine-specific training typically is available at equipment makers’ training centers, as well.

“We work with (our customers’) technicians and help gradually train them,” says Paul Block, vice president of sales strategy and product planning for Global Systems Group, the machinery division of Carthage, Missouri-based Leggett & Platt Inc. He adds that the most successful technicians combine “native talent with very particular skills, many of which you must learn on the job.”

Machinery majors now offer videos that demonstrate equipment operation and basic maintenance.

Lawrenceville, Georgia-based equipment supplier Atlanta Attachment Co. said it constantly adds to its instructional video library, which attempts to address frequently asked questions about specific machines.

The company also operates a hotline staffed with technicians, and after-hours emergency service is available.

With laptop screen sharing and mobile devices, equipment companies can provide virtual assistance to operators and mechanics with equipment problems.

“You can ‘remote into’ any piece of equipment hooked up to a computer or with some type of servo control,” says Hank Little, Atlanta Attachment president. “Our team also uses Facetime a lot to assist mechanics in need of help.”

According to Block, “Screen sharing with GSG technicians is available. You can actually hand over control of the equipment to the technician for help diagnosing a problem. You can also use (the camera in a) GSG tablet to walk around a machine and show what problem you’re having.”

One of the most important things that GSG does is offer built-in maintenance software on advanced machines, Block says. “These are preventative maintenance systems that monitor key components of machines, so company mechanics can track, record and schedule maintenance routines. More advanced machines offer on-screen, step-by-step problem solving.

Asheboro, North Carolina-based Piedmont Mattress Equipment, which repairs machines and supplies refurbished equipment, uses collaboration and the screen-sharing software TeamViewer that can be loaded onto any device or laptop to assist manufacturers’ in-house technicians in doing their jobs.

“Say your flanger is skipping stitches and you don’t know how to fix it, TeamViewer is a great way for us to walk a machine operator or an on-site mechanic through a repair. Even just by sharing video and talking on cellphones, you can provide assistance,” says John Repucci, international sales manager for Piedmont.

Atlanta Attachment got back to basics when it created an internal training program called Stitchology 101 that it now offers to its customers’ employees. The popular course teaches the basics of industrial sewing.

The one-week class is held at Atlanta Attachment’s facility and focuses on general stitch types, including lock-stitch, chain-stitch and safety-stitch. Students learn about stitch formation, the applications for each type of stitch, commonly used threads and needle types. It’s geared toward anyone on the production floor. “You have to invest in training. We constantly train our people—that’s the real solution. When someone starts, they need training, and they need regular refresher courses, too,” Little explains.

Global Systems Group offers technical training on the operation and maintenance of its machines in classrooms and on the factory floor at learning centers in Sunrise, Florida, and Carthage, Missouri.

“People come in from around the world and we give them very specific courses aimed at their skill level,” Block says. “For someone learning quilters and the basics of maintenance, we have a very specific course that’s tried and true; then we have more advanced courses that get into electronics.

“We also have very specific equipment-focused courses where we’ll design training based on the equipment they need to learn.”

Pop quiz

Are you mechanically inclined?

A. It increases

B. It stays the same

C. It decreases

D. It reverses

E. Impossible to tell

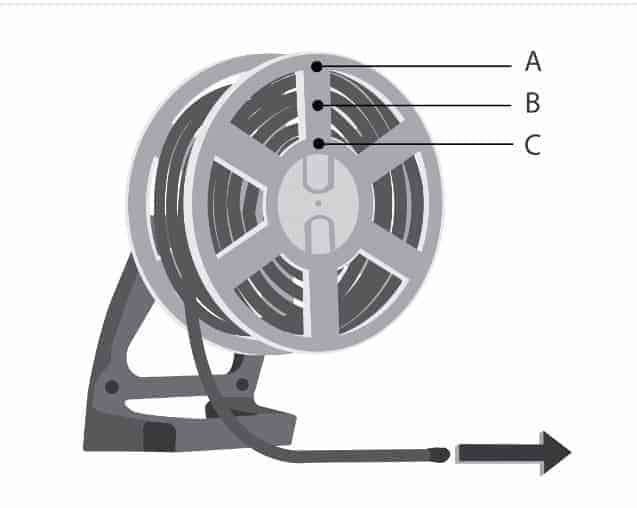

2. When the end of the hose is pulled in the direction of the arrow, the hose reel disc also rotates. Which point of the hose reel disc moves the fastest?

B. Middle right

C. Bottom right

D. They will all move

equally fast

E. Impossible to tell

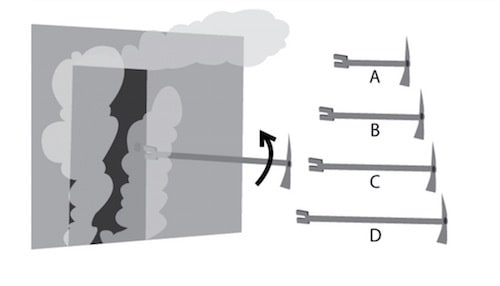

3. Firefighters use a Halligan to forcibly enter locked doors during fire rescue operations. Which Halligan would require the least effort to forcibly open the locked door?

B. Top middle right

C. Bottom middle right

D. Bottom right

E. They would all

require the same effort

Answers: 1. C 2. A 3. D

Source: TestPartnership.com

Resources/Learn more

- Campaign to Invest in America’s Workforce, AmericasWorkforce.org

- CareerOneStop.org, “Funding Employee Training” section, a website sponsored by the U.S.

Department of Labor - Industry Week’s “Skilled Worker Shortage” series

- Marketplace.org from American Public Media, “Manufacturing Is Alive and Well in Reading, Pennsylvania,” Feb. 7, 2017, Amy Scott

- Marketplace.org from American Public Media, “Facing Skills Gap, Employers Send Workers to College,” Feb. 28, 2017, Amy Scott

- National Fund for Workforce Solutions, NationalFund.org

- National Skills Coalition, NationalSkillsCoalition.org

- The New York Times, “Wanted: Factory Workers, Degree Required,” Jan. 30, 2017, Jeffrey J. Selingo

- “Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs: The Skills Gap and What Companies Can Do About It,” Peter Cappelli. Wharton Digital Press, 2012